ppp21 / January 14, 2022

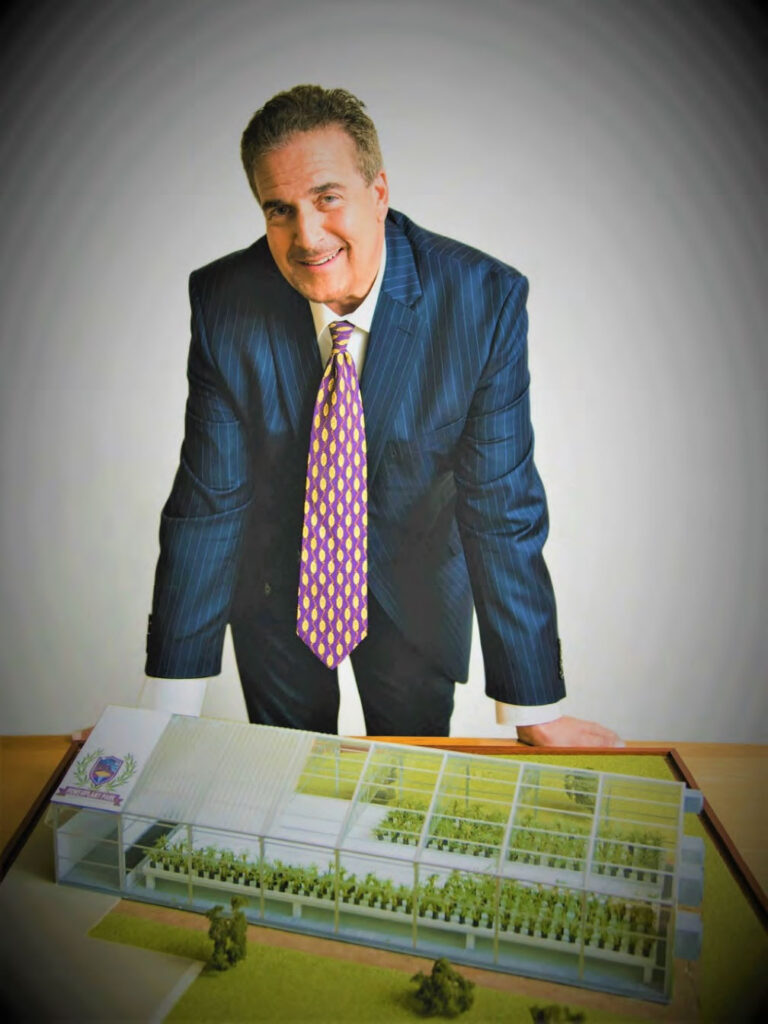

Cannabis and Community – Richard Trieber Founds PowerPlant Park

Campus in Richmond approved for seven different types of cannabis licenses….

Like most parents, Richard Trieber is willing to try anything to do what’s right for his children. Unlike most parents, that led him to a career in cannabis—and running the first cannabis facility of its type in California. When Trieber’ son was in 3rd grade, he started displaying issues at school. He could not focus, and he sometimes distracted other students. “He wasn’t a bad kid; he wasn’t a mean kid. He was just very distracted, and he couldn’t behave in class the way he needed to behave,” says Trieber.

Doctors all recommended ADHD medications like, Strattera, Adderall, Concerta and Wellbutrin. Trieber agreed, but the more research he did into the medicine, the more concerned he became. After several years he worried about the long- term effects of stimulants on his son, and there was no measurable impact on his sons ADHD. He wanted to find an alternative.

In his research, Trieber stumbled upon early evidence that cannabis was an effective treatment for ADHD in kids and was fascinated. He was not even a consumer of cannabis himself at the time, but the data was compelling. It took some convincing to get his son’s mother on-board, but eventually Trieber decided to try cannabis as a treatment for his son.

Trieber began giving small doses of cannabis to his now teenager—and found it much more effective than the prescription medications, (cocktails) he had been given. Trieber’s son became one of the youngest people, (13) in California to receive a doctor’s recommendation for cannabis from MediCann, and Trieber was hooked on the power of cannabis as medicine.

Trieber’s experience working with his son to manage his ADHD and succeed in school eventually led him to work in the cannabis industry. A serial entrepreneur, he had founded mission-driven startups like Local Heroes, a software that allows people to receive discounts at local businesses and donate a percentage of the discount to local charities of their choosing.

Trieber’s experience working with his son to manage his ADHD and succeed in school eventually led him to work in the cannabis industry. A serial entrepreneur, he had founded mission-driven startups like Local Heroes, a software that allows people to receive discounts at local businesses and donate a percentage of the discount to local charities of their choosing.

He took his experience in business and his lifelong connections in the Bay Area—his family has been in the area for generations, and his grandfather was San Francisco’s police chief in the 1920s—to develop PowerPlant Park, a massive campus of marijuana growers and product creators that will be the first legal development of its kind in the state.

PowerPlant Park is an 18-acre, 818,000-square-foot campus along the San Francisco Bay in Richmond, which has been approved for seven different types of cannabis licenses. Craft growers, canna-investors and cannabis brands can lease directly from PowerPlant Park and avoid a years-long process to be approved by the municipality. “We are the first type of facility like this in the state and very possibly the entire country, and because of that we just have unfettered opportunity,” says Trieber.

PowerPlant Park reflects changes in the cannabis industry as a whole. Since cannabis was legalized in California for recreational use in 2016, it has become much more mainstream, and the science of creating cannabis products has developed in record time. “It’s all changed in such a short amount of time, because we have more intelligence now about things like lighting spectrums and controlling the spectrum during the bloom cycle, all the nuances that we are learning about this plant as it becomes more mainstream,” says Trieber. He hopes PowerPlant Park will be at the cutting edge of cannabis science—and at the heart of the fast-growing industry in the state.

PowerPlant Park will be developed in stages, but construction is already underway for the first phase, and 80% of the leases for Phase 1 have been rented. The facility will be open in November. When it is fully operational, PowerPlant Park is expected to bring close to 500 jobs to the city of Richmond. This would make it one of the city’s largest employers, second only to Chevron.

PowerPlant Park will include 59 mixed-light greenhouses, full-service nursery, processing, and manufacturing facilities, all equipped with state-of-the-art machinery for creating concentrates, cartridges, tinctures, prerolls, edibles, and other unique cannabis products for health and personal care. Plans are underway for a 100-driver delivery service, retail storefronts, even two drive-thru sites where people can come directly to the campus to pick up their just harvested orders. Products will include Trieber’s own in-house brand, Transparency, as well as other craft marijuana brands from around the state. Trieber says he will only sell to or involve distributors, retailers, and growers he personally knows to be responsible members of the industry.

The development of PowerPlant Park is a remarkable feat, especially considering how difficult it is to get cannabis-related projects approved. “All of these people in the industry looked at this and said, “you’re out of your mind,” says Trieber. “They told me you have a 2%, maybe 5% chance of getting this developed, (and those were guys who really knew the industry).”

At first, Trieber was just looking for a single building to rent. “I would have been happy with 8,000 square feet, there was just nothing left to rent,” he says. When he could not find anyone to lease to him for a cannabis project, Trieber began to think about building a campus of his own. He knew it would be an uphill battle, and it would take a great deal of time and money.

But after four years of negotiating, and about $4 million sourced from investors and his own funds, Trieber was able to get PowerPlant Park approved and make it a reality. For Trieber, it was almost unbelievable. “It was a really emotional thing then when he and his wife first drove out to site and saw the construction underway for the first time, thinking through everything they had been through in four years of blood, sweat, and tears, it was just an extraordinary feeling. Like, “wow, we are really doing something here,” he says.

PowerPlant Park could be a significant boon to Richmond’s economy since Trieber’s team has agreed to donate 5% of their profits back to the city. It is expected that Phase 1 of PowerPlant Park alone will bring in $4 million in tax revenue directly to the city of Richmond.

Involving members of the community directly in the project is important to Trieber. He has worked with the city of Richmond to develop a diversion program for nonviolent offenders of color, especially those with marijuana-related infractions to be trained at PowerPlant Park as certified cannabis experts. Once trained, the students in PowerPlant Park’s program can work as cultivators or other roles and be paid a starting wage of $27.50 an hour. Their convictions may also be overturned.

“White people might commit the same crime, some kind of drug offense or marijuana offense, but they aren’t punished for it, but black and brown folks are punished so severely in this messed-up system,” says Trieber.

The cannabis industry in California—and in other states—skews white. It’s estimated that about 80% of owners in the cannabis industry are white, while people of color make up nearly half of marijuana possession arrests nationally, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. Trieber’s hope is that programs like his will begin to tip the balance. “If you want to run a cannabis operation, you need to be hiring minority people in your business,” says Trieber.

Trieber hopes that his plans for PowerPlant Park—both his approach to community investment and his model of multiple cannabis licenses in one place—will eventually be adopted elsewhere. “Why wouldn’t we franchise?” he asks. “It would be very easy for us to move the project up and down the state. Eventually, he hopes other cities around the country will want to establish cannabis production parks of their own, 38 states now with some form of legal cultivation. Trieber sees cannabis as a job engine and a tool to lift up entire communities, not as just a recreational drug.

But the truth is, even one location is a dream come true for Trieber. “People looked at me like, ‘get a hold of yourself, Richard, where are you going to get the money?’ But one story led to another. A little money there, a little here, some family money, my wife put in some money she came into unexpectedly. And now, here we are, four years later, and we are building the park. Trieber laments “I was an unlikely person for this to happen to, but I worked my tail off, now the floodgates are open.”